Vincent Gauthier and Pierre Gauthier, Ph.D.

Note: hereafter, the masculine designates both genders.

In our work as leadership consultant and psychotherapist we often come across leaders that are highly aggressive with the people around them. This article highlights the characteristics of highly aggressive leaders, the psychological explanation of such behaviors, and strategies to help aggressive leaders change their behaviors.

Behaviors generally observed in aggressive leaders

The very aggressive leader is characterized by a style that seeks to control, compete, criticize and achieve impossible performance standards. We are not referring here to leaders who have aggressive plans for their units and their companies but leaders whose style is characterized by almost constant aggression towards others.

The typically observable behaviors of the style are frequent demonstrations of anger and irritability such as interrupting conversations, being abrupt and defensive, arguing, and engaging in often physical demonstrations such as shouting and slamming one’s fist on the table. In conversations, highly aggressive leaders are focused on themselves, their arguments and winning the day. They tend to be very poor listeners and are frequently not interested in other’s opinions. These leaders are almost always critical of people behind their backs and use competitive language when talking about others within their own company. For example, they will frequently say of others

- “They do not know what they are doing.”

- “They are idiots and incompetents.”

- “So and so is not to be trusted.”

- “We must win, we are here to deliver results, and work is only about delivering results.”

Aggressive leaders will expect people to execute their orders and will be surprised and irritated when people do not or when outputs are not to their exacting standards.

Such leaders are often boastful and have difficulty giving credit to the team. They very often lead from the front and have the impression that they must drag the team to achieve results. In fact, they almost always complain about the skills, competencies, and ability of their own team.

These highly aggressive leaders will often describe themselves as high performers and will use a language that they believe reflects high performance:

- “I always tell my team they need to perform.”

- “If people are not pushed, they do not perform.”

- “I have no tolerance for low performance.”

- “I have no time to listen to the problems of the team; we are here to get things done.”

Such leaders often have “favorites” in their teams and identify people as “winners” and “losers”. They tend to micromanage the team and bark out orders. As such they usually do not ask for suggestions, listen, or empathize with their team.

Bosses of such highly aggressive leaders often consider them very favorably as hard workers capable of getting the work done. Consequently, the aggressive leaders usually do well in corporate environment and enjoy rapid career progression. In fact, determined in pure business results, they very often enjoy spells of success. Units or departments may perform very well in terms of sales, profitability, market share gain and so on. The issue really lies with what the aggressive leaders leave in their wake and what happens when they quit the organization or move to another position.

They are almost always perceived very poorly by their teams and peers. Their relationships are usually problematic and often end up making them feel isolated. To counter such isolation, aggressive leaders will typically put in place loyal (and passive) followers who support their ascent on the organizational ladder.

From a unit performance perspective, the highly aggressive leaders create several problems for themselves, their teams, and ultimately, the organization they work for.

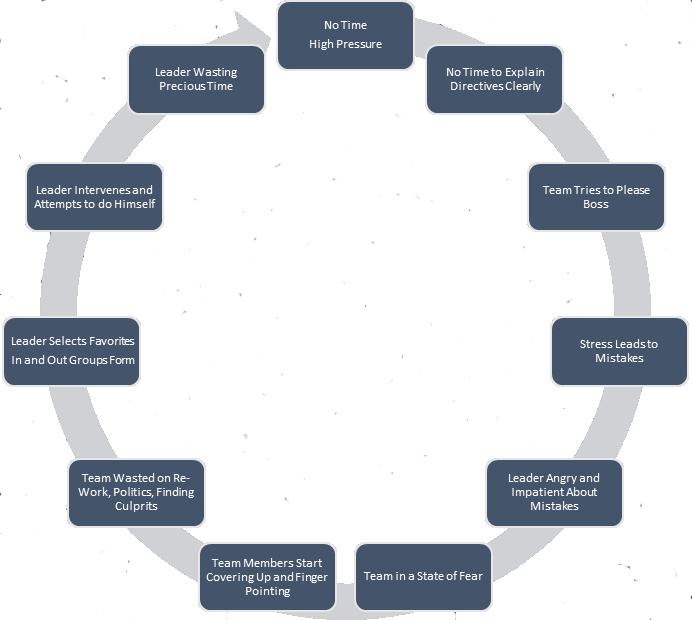

The diagram in figure 1 illustrates the cycle that aggressive leaders create for their units and for themselves.

Figure 1 – The Highly Aggressive Leader Cycle

Because they want to impress and often overestimate their capabilities, they high aggressive leaders will often take on too much work. As a consequence of being in a hurry and being eager to get many things done, they will tend to bark out orders without clearly outlying why a task or project is important, what needs to be done, and how to do it (in case of a first time assignment). In a nutshell, expectations are very typically unclear. Furthermore, tasks are often delegated with a great deal of pressure in terms of timelines, quality of outputs, and the very frequent: “Don’t screw this up.”

The direct reports or the team will naturally feel the pressure coming from the boss and will work as hard as they can to meet his expectations. In our experience, few direct reports purposely try to deliver outputs of low standards, particularly when they know that the boss’s expectations are high. However, since the expectations were not originally clarified, direct reports often struggle to deliver exactly what the boss wants. Furthermore, the team led by an aggressive boss often works under the double pressure of time and high expectations. Under such pressure, people are prone to make mistakes. When an outcome with mistakes is delivered to the highly aggressive leader, he very often gets into a fit of rage as the work is now done without time to fix it. In those circumstances direct reports get a double dose of negative feelings; first because they get no recognition for trying to please the boss, and second because he is displeased with the results of their action. This cycle of high expectations and high pressure, unclear expectations around assignments and, ultimately, reprimand for not doing something correctly quickly leads to the establishment of an atmosphere of fear in the workplace.

In turn an atmosphere of fear pushes teams towards covering up mistakes or blaming them on others. Leaders then start spending more time on trying to find who committed a mistake, why it was committed and so on. However, since fear pushes people to dissimulate, much time is needed to find the cause of the problem; hence valuable time and energy gets wasted. Such finger pointing also leads to recrimination and very soon cooperation and collaboration in the organization come to suffer enormously. We once worked with a leader who proudly said that people did not hide anything from her because they knew she would throw them out the window if they did (her office was on the 22nd floor!). She did confess a bit later that she had to “interrogate” the team when mistakes did occur as no one would dare volunteer the information.

An atmosphere of fear in the workplace also tends to make direct reports conspire together to lower the group standard. Why would anyone do more than is necessary if the outcome of a task or project will almost surely end up with the boss being angry or critical? Fear kills any kind of initiative and creativity in the workplace. In such circumstances people tend to wait for orders. This drift towards group mediocrity ensures no one looks especially bad and spreads the wrath around so each team member gets a bit. This in turn appeals to the group’s sense of belonging – they belong to a group who look after each other. The problem is that the group does not include the leader. Usually, someone else, who can shield the team to some extent becomes the leader. The aggressive boss soon begins to believe that his team is indeed incompetent and starts taking on more of the work himself or else it: “does not get done.” Very often the boss also starts over-relying on a few “loyal” people who can tolerate his attitude. These people become favorites, “the stars” at the expense of the rest of the team. “The stars” take their cues from the boss’s leadership style and reproduce it with their own direct reports thus further contributing to the creation of a culture of fear in the workplace. The creation of “in” and “out” groups also complicates team dynamics and collaboration suffers further.

Finally, the boss, unable to give all his work to a few trusted direct reports, ends up taking on more and more tasks. This reduces his time to accomplish other more important tasks, and he starts multiplying the pressure. The aggressive leader is now under even more pressure himself, takes even less time clarifying expectations and becomes more exasperated. Such a process gradually becomes a negative cycle that may eventually destroy careers, departments and companies. Many aggressive leaders have seen their career unexpectedly come to an end because they have completely lost the trust, good will, and cooperation of their teams. In many cases, we have seen direct reports actively campaign to see their leader fail.

- Sacrifice profitability (and spend money) for the good of their employees, partners, suppliers and the public at large

- Put a moratorium on the pursuit of quarterly results and profitability and open their purses to protect wages, and make purchases and investment when the time comes

- Think about halting stock markets and freezing stock prices until the right time is decided to resume trade

- Halt the repayments of loans and interest for a period

- Be willing to help foot the bill for astronomical medical costs

The making of a very aggressive leader

It is important to understand the underpinnings of the very aggressive leader’s attitude and behavior here described. As we have previously mentioned, this type of leader creates problems for himself, his direct reports, his clients, and his whole organization. To fully comprehend a behavior that does not correspond to rational, functional considerations, one must go back to the very development of a personality. To do so it is worthwhile to examine the beginnings of human development. In this perspective three phases of early life play a crucial role.

- The beginnings of life, from conception to about 18 months after birth. During the period of pregnancy, the physical and psychological welfare of the mother is important for her own development and the growth of her baby; the birth process and the post natal period also exert a determining influence. All of this contributes to create, imprinted within the infant’s central nervous system, a basic pattern of trust or mistrust in his human environment.i

- From about 18 months to 3 years of age.

As the infant matures, he or she ceases to be relatively docile. The age of “no” sets in, whereby the child tries to affirm his own will. Any proposition is likely, at first, to obtain no for an answer. And, as the child’s muscle system is much stronger and better coordinated, the age of exploration sets in. He wants to climb up and down stairs, reaches for everything that attracts his attention, even that precious vase on the table. To cap all of that, the 18 to 36 months period is the time where sons or daughters learn to control their sphincters, to be “clean”. No small feat for a toddler.

Here the parents’ behavior may take diverse directions. The understanding, empathic parents will recognize the child’s efforts toward autonomous decisions and patiently negotiate with him. His attempts to overcome physical challenges such as standing, walking, running, climbing, rolling, doing somersaults will be encouraged, recognized, appreciated. The difficult learning “to be clean” will meet with careful support based on recognition of success and acceptance of failure. Thus, the child will feel that his parents and the other adults he regularly deals with are cooperative, “on his side”. As a result, a conviction, the foundation of self-confidence, will gradually imprint itself in his brain: “I am capable to accomplish, I have the power to make decisions and carry them through.”

At the other end of the spectrum, the parents may hold the belief that the child’s role is to obey rather than learn by doing. So any resistance, such as a resounding “no”, will be met with punishment, verbal or physical. Hence the child registers that his own will is practically non-existent. Worse, he internalizes the conviction that his tendencies to decide for himself, explore, try to do whatever is suggested to him by his immediate environment, that all of this is bad. Since he does not have the mental capacity to establish nuances, he will generalize his conviction to his whole being: “I am bad”. In other words, inhabited by unaccepted tendencies, I have basic defects, I am a bad person.ii

This generates, deep down, a terrific protest in the form of anger that, at that age, cannot be expressed in words. In adult life, this may manifest itself by relentless efforts to prove oneself as superior to others by constantly responding to ever greater challenges, at great cost to self and others. This compulsive need of superiority over others should not be confounded with the innate need for achievement.

- 3 to 5 years of age.

Around the age of 3, the child discovers that he has a sex, like everyone around him. At the same time, he shows interest in the emotional aspects of his relationships with mum, dad, brother(s) and sister(s) or their substitutes. He is very curious about the emotional components of those close to him.

He expresses his affection to those who are significant to him. Very often the little child feels great love for his natural or substitute parents and other close relatives, but this early love development does not happen automatically. It requires an environment where people of both genders treat her with interest, attention, affection and stimulation that respects her sensitivity. Then the child behaves like a little lover or a little lover with those he chooses.

This announces that the child becomes aware of his feelings and those of others; it evolves towards the capacity to establish relationships based on emotional openness and reciprocity. Both the boy and girl want to behave in ways that will please their loved ones and need encouragement for what they are doing. Previously they were rather egocentric, now they are beginning to understand the feelings of others, they are learning empathy (the ability to feel another person's emotional state while remaining aware of themselves and their own emotional climate). For his evolution to be as complete as possible he must develop his awareness of the effects that his actions and words can cause to everything that exists: humans, animals, plants, inanimate objects. Already he can feel compassion and try, within the capacity of his means, to help others around him who are in need. Once again, it is by being treated with empathy and compassion at a very young age that children learn the basis of their adult leadership.

- Early School Years (6 to 12)

During that period the child gradually takes interest in learning in a systematic way. He or she learns the procedures of reading, writing, calculating, doing “scientific” experiments and so on. They also begin to learn how to act in a group situation, how to play games with winners and losers, they start using defensive, offensive and mediation tactics of conflict resolution. Expressive activities also allow them to explore their talents and present the fruits of their creativity to others.

The flip side of this development is experienced by the child, male or female, who finds he is repeatedly unsuccessful in learning activities. Or he may be adept at physical feats but get poor results in academics. Then he will concentrate on his area of success, investing very little in acquiring more attention demanding pursuits of knowledge. If he is unsuccessful in practically all school related activities, he will develop hatred of anything connected with systematic learning, including teachers, other youngsters who succeed and knowledge or performance.

- Adolescence

All this development greatly increases during adolescence, both cognitively and affectively. From the emotional development point of view love for parental figures becomes more realistic in the sense that “marriage plans” with a parent or sibling are renounced in favor of romantic links with partners outside the family circle. It serves as a basis for taking initiative in numerous domains, such as acquiring knowledge and a variety of skills used in the occupational world.

When such evolution does not take place a sense of guilt about sexual tendencies and inferiority in social relations is strongly felt, confirmed by failures in attempts to establish intimate relationships with friends or potential love partners. In turn this provokes a retreat into oneself accompanied by grandiose dreams of power, both in the socioeconomic and romantic fields. In daily life, authentic rapport with others is replaced by formal politeness and mock interest.

The personality and behavior of the highly aggressive leader

What is the relationship between the areas of personality development just described and the behavior of a highly aggressive leader? Let us try to construct a schematic view of the personality development of the highly aggressive leader during his formative years.

In early infancy, he has received enough care and attention to be protected from severe emotional defects but has not experienced warm emotional bonding with at least one parental figure. Consequently, he has not internalized an experience of intimacy. When he reached the “age of no” (18 months to 3 years) his attempts at opposing, affirming himself and “being the absolute boss” have been met either by very aggressive reactions where he was totally dominated, or by a laisser faire attitude where he gained a conviction that indeed he could impose himself on everyone. The result is an enduring dominant-dominated pattern in his relationships to others: every encounter is lived as a test of who will supersede whom.

At the age of 3 to 5, the dominant-dominated pattern was not replaced by rising consciousness of others’ feelings, the base of empathy. On the contrary, in this period of his life he may have learned to dominate by manipulating others’ feelings rather than be emotionally open. During school years academic and sport activities were occasions for tough competition with others, with as little cooperation as possible. The result was success in those activities, reinforcing the conviction that life is a basically a contest to be won, with a tendency to despise “losers”. Adolescence brings the rush of hormonal waves and the resulting discovery of sexual desire, plus some access to adult prerogatives, where revenue producing, and romantic endeavors confirm the dominant-dominated attitude. Again, at that age, our highly aggressive leader probably engaged in great efforts to be part of the dominant club, to fight for grades, money and romantic partners as trophies. So everything was in place for him or her to enter the workplace with great ambitions to reach top positions. Hard work produced its rewards and top positions became a reality. He or she has become a member of top management.

To further understand the inner dynamics of the highly aggressive leader, let us keep in mind that personality development unfolds like biological growth in a spiral fashion, phase 1 serving as the basis for phase 2. The second phase integrates new development arising from the one already existing; it thus creates a basis for phase 3, where new elements will be acquired, synthesized with the components of phases 1 and 2, and so on.

So, let us imagine that, from conception to adulthood, an individual has gone through phases of development that were mostly positive. The probability is great that such a person will become quite adept in human relations and the other skills required to be a good leader. If he is given a post where he exerts authority, he will tend to take at heart the objectives of his organization and work towards attaining them. How? By being technically competent and by motivating his subordinates to also do their best in the accomplishment of their jobs. He will combine goal attainment with care for the personnel involved.

Here many people think of money as the great motivator. Of course, it plays a crucial role. It is a necessary factor of motivation but alone will not succeed in bringing people to be proactive, cooperative and creative in their work. The other prime factor is the quality of human relationships established in the work milieu. And in this domain the leader may exert a very positive influence or, on the contrary, involuntarily hinder energy investment by people who work at his level or under his authority. Furthermore, in any organization leadership style tends to ripple down from the top leader to the various levels of authority under him. Mid-level managers will treat workers in their charge as they themselves are dealt with by top management.

So a top leader has the potential to create in his organization a work atmosphere where the individual worker feels part of a larger group. Then the worker

- feels a sense of belonging and solidarity

- pays attention to the quality of the products or services produced with his participation

- is considered as an individual with rights, competence, ideas, a sense of responsibility

- participates in a group oriented towards productivity and creativity

- willingly participates in the development of his organization.

What has just been described is called an ideal model. It cannot be found totally realized in a given work milieu but serves as a guiding light for the whole organization, from top management to first level workers.

The above-mentioned outline can tell us how detrimental a very aggressive leader can be, for he does little or nothing in the way of creating a motivating culture in the company. Why such blindness and deafness to the basic elements required for building a constructive culture? Most probably because the leader has developed a personality imbued with an attitude of mistrust and antagonism to human contact, defining every encounter as a match to decide who will win, who will lose. If he learned in his young years that the best defense is quick counterattack, this will be his reaction when he feels in danger. Or he will retreat in sullen solitude, become unreachable. In other aspects of his work he may have developed high competence. Also, during his phase of life where he was up and coming, he may have learned to convert anger into positive action, thus earning praise by his bosses and nomination to posts of responsibility. In almost literal terms he has fought his way to the top.

But once at the top, problems start to accumulate for he lacks the social skills to motivate the people in his organization. Not being able to really listen cuts him off vital information. His tendency to counterattack or isolate when he feels in danger creates a social void around him: he gradually loses the support of highly competent assistants with a sharp sense of their own value. They expect to be treated in a considerate, cooperative manner. If this expectation is not met in day to day encounters with their leader, they find work elsewhere or, little by little, he replaces them with subservient people who exert little or no creativity. His constant quest of dominance in every encounter turns off lower level workers and their representatives so personnel morale tends to decline, resulting in high absentee and turnover rates, accompanied by serious declines in productivity as workers, consciously or not, tend to lower standards.

Faced with little support by incompetent but docile assistants, unable to motivate and keep competent first line workers, the highly aggressive leader quickly faces bad business results. Under even more pressure, he reverts to the only style he knows, one that has brought him “success” till now; he becomes more aggressive and bullies those around him even more, thus perpetuating the vicious cycle… Ultimately such leaders can bring massive organizations crashing down.

Strategies for personal change of the highly aggressive leader

His greatest temptation is to look outside of himself for culprits to whom he can attribute the decline. That will only aggravate the problem. A much more productive move is to “go inside”, to introspect. Is there something in my personality that puts me in trouble as a top leader? If so, what can I do to change that?

Hence the first move is internal, where the leader is not examining other persons’ behavior but his own, especially in the field of interpersonal relationships. The aggressive leader must recognize that there is a problem and that he can become more effective by changing his style of leadership. Without this self-awareness the leader will not change. Many companies have tried to dictate behavioral change on aggressive leaders with very little success. The decision must be personal, and the leader must recognize that he is part of the problem. Very often this recognition can be prompted by a number of circumstances: difficulties at home with spouse and children, a 360 feedback showing clearly that the leader has lost the cooperation of his peers and subordinates, or repeated feedback from trusted advisors about problematic behaviors leading to negative results.

Once the leader has developed increased self-awareness, he may take time off work for a short period, a few days or a few weeks, to retreat in a quiet, pleasant and secure place. There he reflects on his whole life, past, present and future. This will allow him to contact memories of his past where he has been emotionally deprived or abused, to examine his present situation, professional and personal, and his near future. Such facing within can also take place without quitting the work scene, by allowing oneself a few periods of undisturbed reflection during the day. In fact, experience shows that effective leaders often take 5 or 10 minutes per day of undisturbed time to reflect on issues, people, and events.

An approach that focuses primarily on introspection rather than on finding responsibility other than oneself can cause a great deal of anxiety, sometimes to the point of anguish. But if the aggressive leader dares to overcome this barrier, he will be able to identify major sources of his difficulties with colleagues, employees or clients.

To push his search further he may seek the counsel of one or two persons (coaches, psychotherapists) who have acquired competence in relationships with self and others. There is a reason for such suggestions: if the leader is very aggressive, his attitude and behavior probably developed during his formative years, by living in close contact with people who had not acquired high quality communication skills, hence could not transmit them to him. He was therefore unable to acquire during this period of his life a strong capacity for self-regulation, empathy and compassion, three indispensable resources for understanding and motivating his fellow human beings.

Should he feel condemned to failure because of this? Not in the least, for interpersonal competence may be acquired at any age, in active and regular contact with chosen people who will provide him occasions to learn how to self-regulate his anger, and how to develop authentic empathy. Two major questions to be examined by the aggressive leader: what are the present and past sources of my aggressiveness, how to regulate it in the actual situation? Many techniques and activities are effective to progress in self-regulation in the face of attacks, real or perceived as such. The whole area of aggressiveness integration and expression while maintaining emotional contact with the interlocutor(s) is here a major area of “work on self”.

One successful coaching process involves the leader enlisting help and feedback from peers, subordinates and bosses to coach him on the desired behavior. The leader must first recognize that he needs to improve the quality of his relationships with others, highlight those areas with trusted advisors and define with them how he prefers to be coached and monitored on improvements.3 It is also important for the leader to understand his strengths and focus on developing them further. An aggressive leader, for example, may have an exceptional ability to foresee the future of his company. Such ability to create a vision should not be forgotten for the sake of focusing on shortcomings. Shortcomings can be managed while qualities or strengths continue to develop.

However, few executive coaches have the training and experience required to deal with more fundamental personality disorders. In such cases, the leader may seek the help of psychotherapists or other professionals.

We are here at the junction of individual personality traits and organizational accomplishment. A leader who is incompetent in human relationships may do limited damage to his organization if he is at a low level of authority. But as he ascends the authority ladder, his shortcomings have more and more influence on the fate of the organization he belongs to. Conversely, a relational leader centered on goal attainment and authentic care for the personnel involved will lead his organization through a durable series of achievements.

Vincent Gauthier: Founder, Insight Leadership Inc.

Pierre Gauthier, PhD. Psychotherapist

References

Schore, A.N. (1994). Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self. Hillsdale, N.J., USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Van Winkle, E. (2009). The Biology of Emotions. http://www.redirectingself therapy.com/anger.htlm

- Solomon, M.F. & Siegel, D.J. (2003). Healing Trauma. Attachment, mind, body, and brain. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Goldsmith M. (2001), Helping Successful People Get Even Better! (Modified from Leading for Innovation, Hesselbein, Goldsmith and Somerville, Jossey-Bass)